A guide to becoming a senior product designer

This is how career ladders work and how to create a career plan to climb the ladder.

Hello, I’m Felix! Welcome to this week’s ADPList’s Newsletter; 🔒 subscriber-only edition 🔒weekly advice column. Each week, we tackle design, building products, and accelerating careers. If you’re interested in sponsoring this fast-growing community, let’s chat!

Q: What’s the path for me to become a Senior Product Designer?

I recently read an article about getting into the role of Senior Designer by Aaron James, Senior Product Designer at Netflix—and I was blown away by how insightful and powerful his thoughts are. As I dug in and chatted with designers on ADPList, I thought this was a powerful yet underserved topic anyone spoke about.

Aaron was very kind to agree to me to feature him as a guest writer on “A Guide to Becoming a Senior Product Designer.” Aaron has worked at Hulu, Meta, and now Netflix and is a distinguished mentor on ADPList. Lots of insights he has to share on this topic.

You can find Aaron on LinkedIn or Medium!

TLDR; what you can take away from this post:

Product design career ladders are unique to each company. Some will have a well-defined ladder, while others don’t.

The stereotypical rungs of the ladder are Junior, Mid-Level, Senior, Lead, and Principal.

The reason there are rungs in the ladder is to clarify design expectations, share what a company values in a designer, calibrate designers for interviewing, and give designers a sense of career progression.

The higher the level, the more experience and impact a designer has.

Leveling up doesn’t happen by accident. You must create a career plan.

A career plan captures your weaknesses and how you can improve them.

To create a plan, assess your current level, study the expectations of the level above yours, and create actionable goals to level up your skills.

Check-in on your plan every three months to see if you’re on track. Only expect to level up once a year.

If you’ve stagnated, you can refresh your plan, find new projects, find a new team, find a new company, or find a new career path.

Let’s dive into it! 🙏

Overview

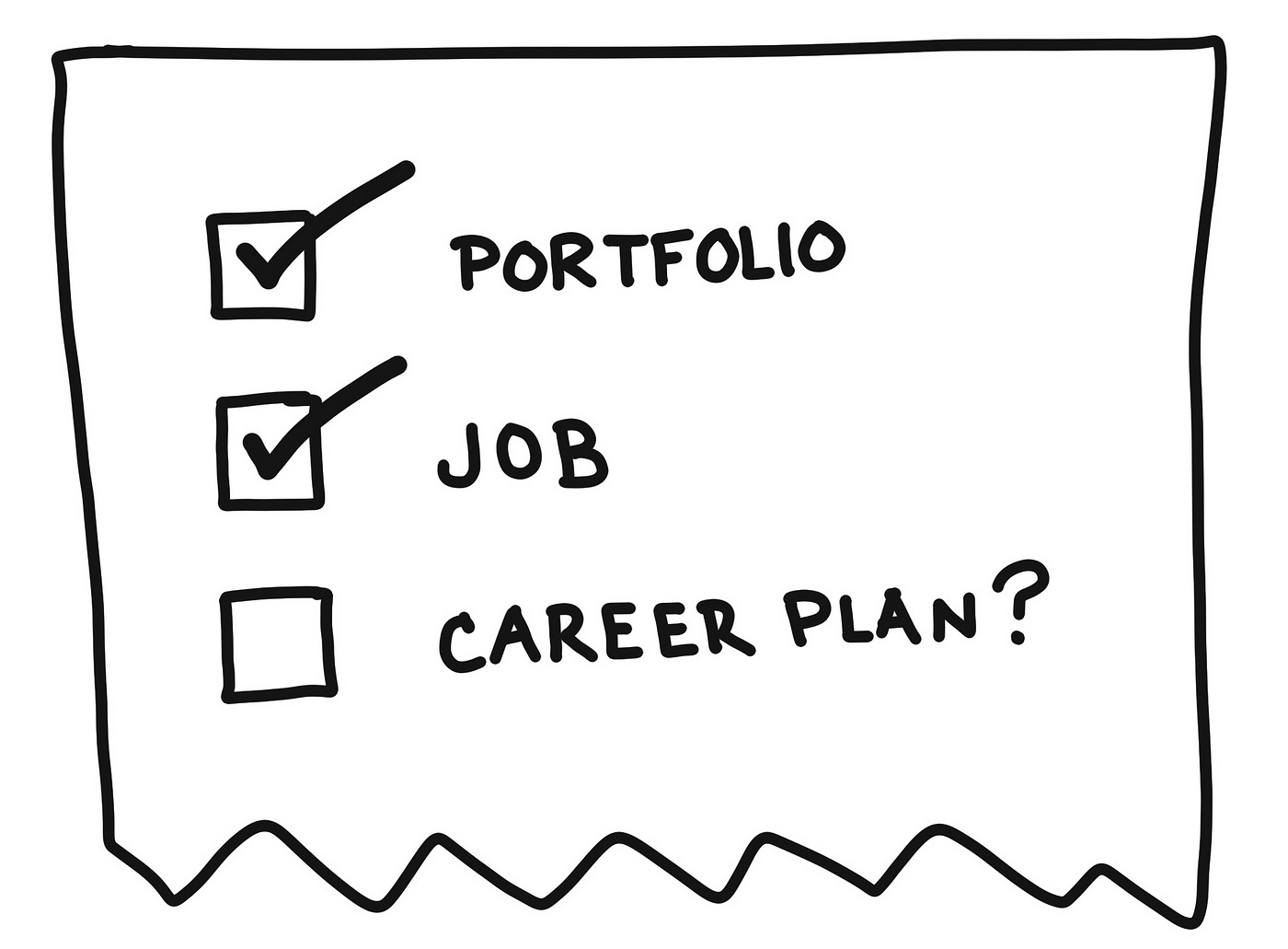

By this point, you’ve likely created a compelling design portfolio that got you noticed by companies. You’ve hopefully been asked to interview at those companies and aced one or multiple interviews. In a perfect world, you work for a company as an individual contributor. Now what? It’s time to begin thinking about your long-term career goals and how to achieve them.

You’ve likely asked yourself, “How do I grow and level up to become a senior designer?” and that’s what I’m aiming to answer here. This article intends to give you the tools you need to understand the design career ladder, assess your current level, give clear guidance on how to level up and be an evergreen resource you can reference throughout your career. Leveraging this article can keep you on track and accelerate your career growth as you climb higher and higher.

A Note to Designers

If it’s early in your career, you can set career goals and begin planning your career path but I want to emphasize something important first. Your primary goal early on is learning marketable design skills and collecting projects with real-world impact. You should expect your early years to be a grind which means senior-level design may seem out of reach for you. That’s normal. Until you find a job that has a stable design ladder, it’s difficult to level up. Don’t let this fact dissuade you from becoming a designer though. Eventually, your career path becomes clearer and each rung in the design ladder becomes more tangible.

Your design homie,

Aaron J-dawg

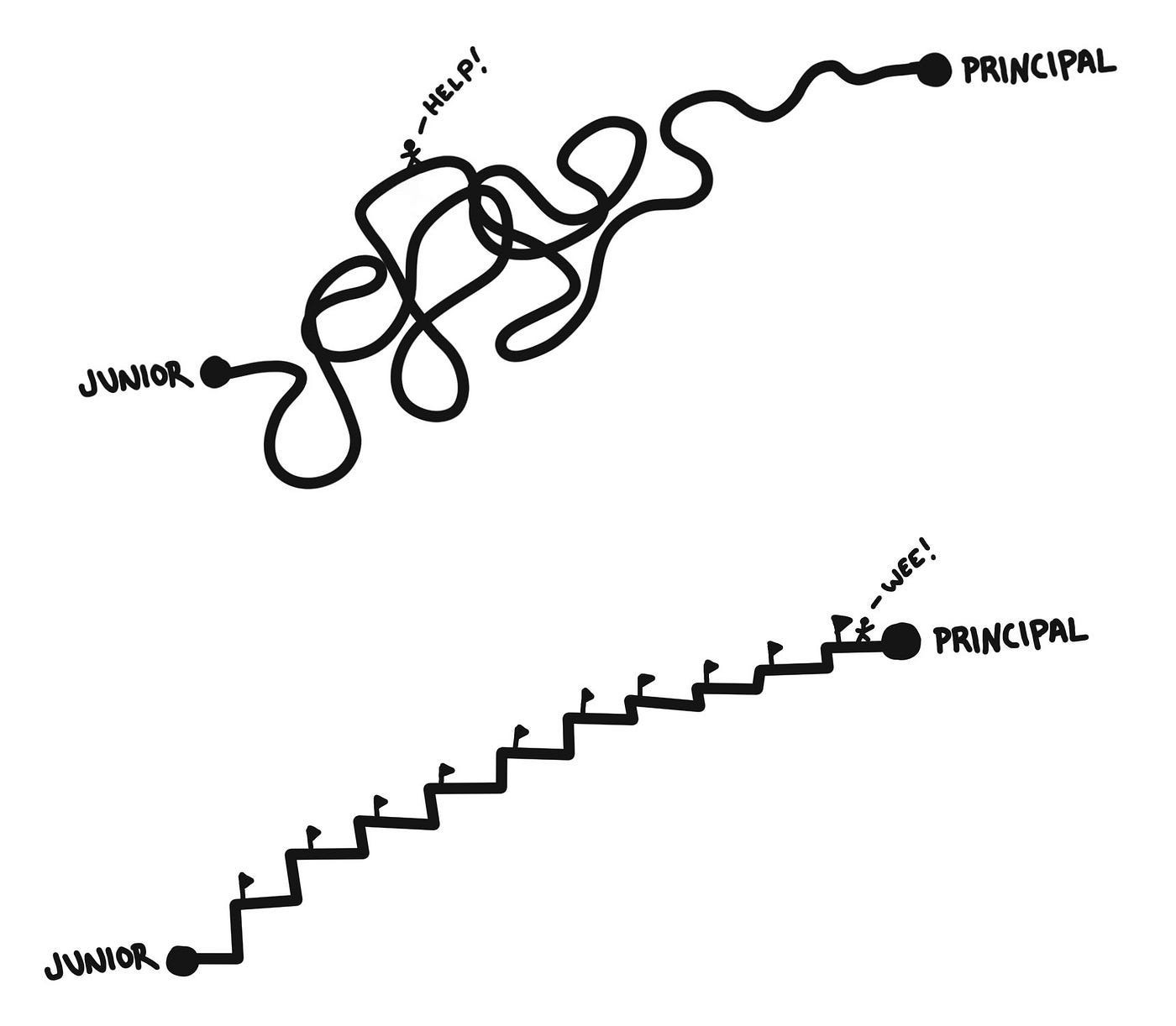

The Design Career Ladder

Multiple metaphors are used in the design industry to describe design career paths and how they’re organized. You’ll hear people speak about career paths as “stairs and steps,” “ladders and rungs,” “levels and experience,” and so on. These metaphors convey that as you gain more experience and impact in design over time, you ascend the ranks upwards to more senior positions at a company. For the sake of this article, I’ll use the “ladder and rungs” metaphor to describe the design career path and images of “stairs and steps” to confuse you. Lol.

As you gain more experience and impact in design over time, you ascend the ranks upwards to more senior positions at a company.

All Ladders Are Different

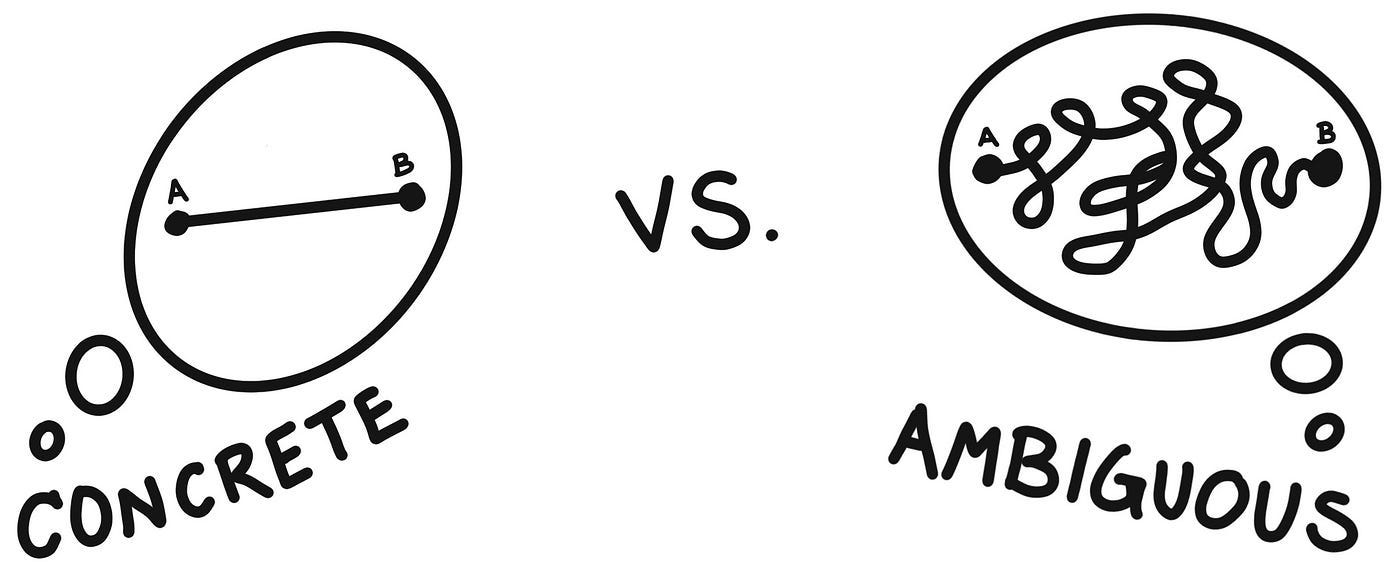

Once you’ve landed your new job, one of the first things you should seek out is your design-level expectations. These expectations will give you a clear sense of the design ladder at the company. A mature company will have these expectations documented and accessible to all designers. Every company’s expectations will vary and have different definitions for each level. Some documents will be more granular and specific, while others will be more generalized and ambiguous. The more specific the design expectations, the easier it is to create a plan for leveling up. The more ambiguous the design expectations, the harder it will be to level up without manager support. Lean on your manager to bring clarity to these ambiguous expectations.

Undefined Ladders Can Seem Chaotic

Companies that don’t set clear expectations for their designers will sow chaos for their designer’s career path, or at least it may feel that way. Without these expectations, inexperienced designers will not know how they’re performing, if they’re having a positive business impact, providing real value to the company, or how to interview other designers on the companies behalf.

These companies may use subjective bias as promotion and hiring criteria instead of objective and measurable criteria. That’s not to say this is necessarily a bad thing, though. Some will love the freedom and ambiguity as it presents an opportunity to lead and skip levels, while others may struggle in these environments. I don’t consider the lack of a defined career ladder a red flag, especially if you’re more experienced in design. Undefined ladders may just be a byproduct of a compani’s scrappy nature or their recognition that ladders contribute to competitive and stressful environments—more on that in a bit.

If you’ve joined a company that doesn’t have documented expectations for designers, and you crave the structure of a formal design ladder, work closely with your manager to define your role expectations and what it takes to level up. Lack of documented expectations is also an opportunity to lead by creating expectation documentation for the entire company. The exercise of creating this documentation will help you level up as well since more senior designers and managers typically create this ladder documentation.

The Ladder Competition

Some companies choose not to have a formally documented ladder available to their designers and for a good reason. The designer career ladder can quickly become weaponized and result in competitive behaviors. This competition occurs when designers compare themselves to other designers—which is not how designers should use the ladder. It can lead to designers straying away from impactful work in favor of chasing vanity from titles at higher levels.

The designer career ladder can quickly become weaponized and result in competitive behaviors.

Some companies will take this one step further and ask their designers not to disclose their level with others. The intention behind this task is to remove the off-chance of designer competition and pressure to perform. Ultimately, competition will lead to hostile and stressful work environments, contributing to less creativity and design output if left unchecked.

By the way, you can opt out of ascending the corporate designer career ladder altogether, too. It’s not the only path into the design industry. Those who choose not to enter the corporate designer rat race will often freelance, join early-stage startups, or join smaller design agencies. Not conforming to the definitions of a traditional ladder has its benefits. For example, there’s no pressure to perform, leading to more creative freedom and expressiveness.

That all said, the benefits of knowing the career ladder and understanding how to properly use it far outweigh the cons, in my humble opinion—especially if you are earlier on in your career.

The Rungs in the Ladder

For the sake of this article, we’ll use the boilerplate levels of Junior, Mid-Level, Senior, Lead, and Principal product designer. These titles are considered the stereotypical rungs in the designer career ladder and represent many things to many people. But primarily, these titles represent a designer’s experience and the amount of impact they have.

Why Are There Rungs?

This question is a wonderful one that points directly to the heart of this entire article. The reason there are rungs in this metaphorical ladder (or levels) is to:

Clarify responsibilities and expectations: A company with documented responsibilities for each level sets clear expectations for its designers. These expectations help designers understand how they should contribute to their teams and company, giving them a sense of perspective for their role and how they can grow.

Clarify the traits a company values: A company with documented expectations explicitly shares what they value in a designer. This beautiful fact makes it easier to understand if your role has a business impact by contributing directly to a product or has an impact by designing presentation decks and “making things look pretty” for product teams. By the way, I’m not saying the latter is necessarily a bad thing. A designer has to create Apple’s beautiful keynotes, after all. But, instead, what I’m saying is you’ll know if the company’s values align with yours.

Calibrate designers for interviewing: A company that has documented expectations for designers at each level can use them as a calibration tool for interviewing. The expectations help interviewers understand if the candidate measures up. It gives concrete expectations for if the design candidate should be hired for the role. Without these expectations, it’s tough to have objective conversations about whether or not the company should hire a design candidate without referring to one’s “gut instinct” or “past experiences,” leading to unfair hiring practices.

Give a sense of career progression: Finally, a company with documented expectations gives designers a clear goal to achieve. They can reference the level expectations above theirs and create a concrete career plan with actionable steps for leveling up. Without these level expectations, it’s like shooting in the dark at a moving target while standing still. It becomes much harder to progress in your career without defined levels.

Level Differences Between Companies

The rungs of the ladder aren’t standardized across the entire design industry. Not every company uses a boilerplate structure, and the level of expectations will change depending on the company’s values. Another variable I’ve come across is how granular the levels can become. Some companies will have many more levels, whereas others will have a flat organizational structure with no levels at all. Here are a few ladder structures, for example:

Junior, Mid-Level, Senior, Lead, and Principal

Assocoiate, Staff, Principal

L1, L2, L3, L4, L5, L6

IC3, IC4, IC5, IC6, IC7, IC8

D2, D3, D4, D5, D6, D7, D8

D101-110, D201-210, D301–310

If that list didn’t make sense to you, join the club. I have no idea what those last ones mean. But you know what, these structures don’t matter in the grand scheme of things. So next, I’ll help you understand the skills all designers possess.

Lead & Principal Levels are Temporary

Can I tell you a secret? The highest levels on the product design career ladder are super subjective and open to interpretation. In addition, those titles are ephemeral and may change from one project to another or one company to another. I’ve met designers with the title of Principal that operates like a Senior designer and Senior designers who I’d define as a Principal designer— mainly because of how they contributed to some of their projects and the momentary impact they had in the past. If you conflate design industry influencers with designer titles, this conversation becomes even more complicated.

I, too, have held the title of Lead designer on multiple occasions but do not consider myself a permanent Lead designer. It’s my opinion that these upper levels are ones you flex into as needed, and eventually, you fall back to the Senior level. This is why I believe they’re ephemeral. I’m open to being wrong, though. So if you want to have a discussion here, let’s hash it out.

Why does this matter anyway? Well, if you made it to the Senior level, I consider you near the top of the product design career ladder for individual contributors. So make sure to celebrate once you hit this level. Huzzah!

OMG. I just discovered boogers on my chair. How is that even possible?

The Ladder Building Blocks

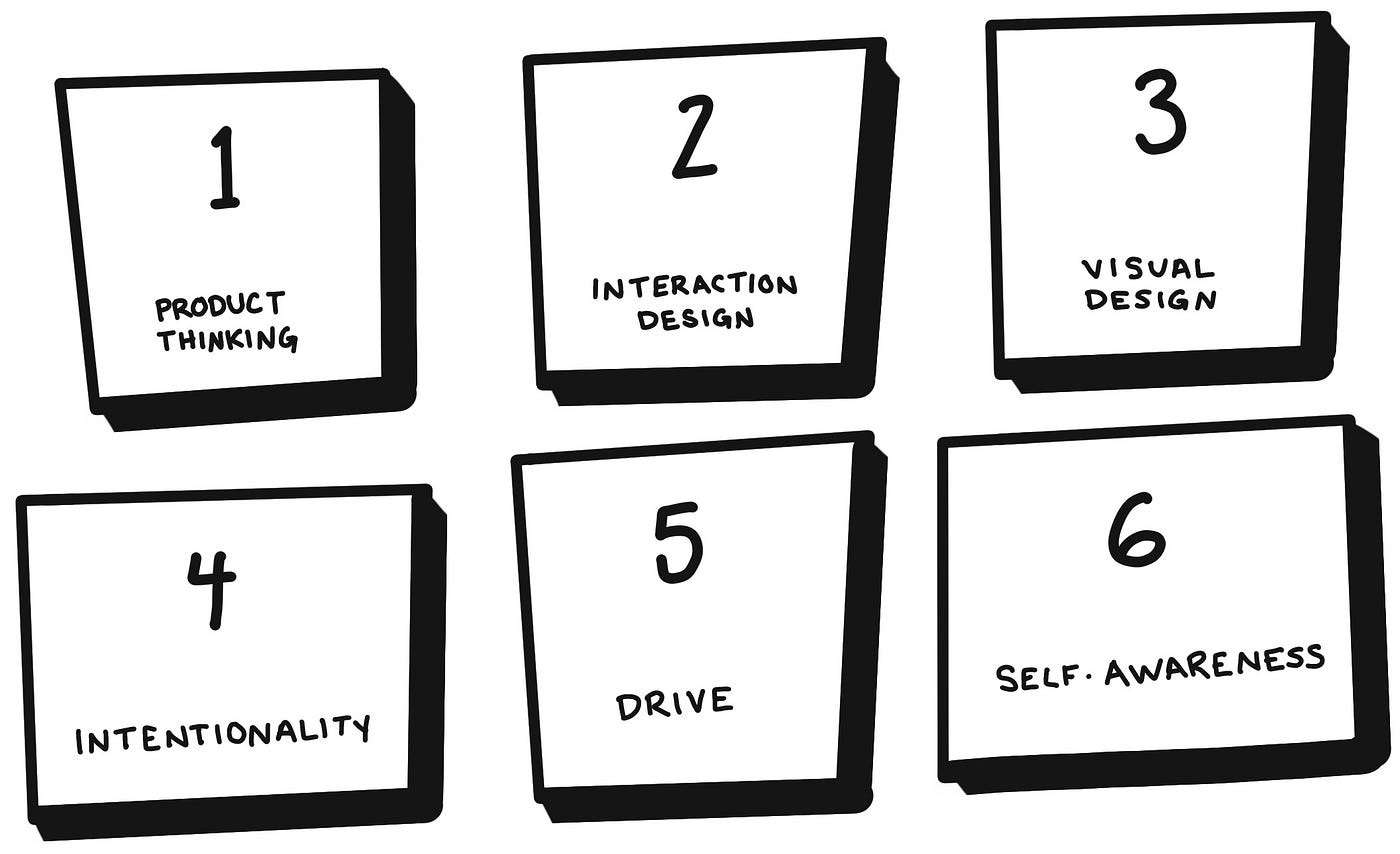

In past articles, you’ve seen me describe designer skills through the lens of “design axes.” These are the fundamental building blocks of the product design career ladder and are every product designer's skills. They’re common between us all, regardless of level. These design axes include a designer’s hard and soft skills, which are defined as follows:

Hard skills: They’re techniques and knowledge you learn while in design school or on the job. They’re used to perform the “act of design.” For example, the skills related to using design tools, design software, pencil-and-paper, etc. If you can touch it, it’s a hard skill.

Soft skills: They’re more ambiguous and challenging to master. These are related to your personality, people skills, and work ethic. You’re life experiences shape these skills and contribute to your overall emotional intelligence and self-awareness.

The high-level design axes that I learned from good ol’ Papa Zuck are Product Thinking, Interaction Design, Visual Design, Intentionality, Drive, and Self-awareness. It’s important to know that these six axes are a mixture of your hard and soft skills. So let’s dive deep into design axes next. Each axis will have a link to my boilerplate Product Design Level Expectations Rubric for reference.

The reason it’s important to know the design axes, is because they’re what you must continually strengthen to level up as a product designer.

1. Product Thinking

The skills related to Product Thinking encompass how to create successful products by solving user and business problems. Within this axis, there are three distinct sub-categories:

User: A skill to understand the people who use the product and the problems they face.

Business: A skill to understand business opportunities and ultimately generate revenue directly or indirectly by solving user problems.

Strategy: A skill to understand how products should be strategically designed and launched to reach product-market-fit.

2. Interaction Design

The skills related to Interaction Design encompass how to design for people and their behaviors. There are three distinct sub-categories here within this axis:

Patterns: A skill to understand people’s behaviors as they interact with the platform a product is built upon and design solutions around these behaviors (e.g., mobile patterns, web patterns, accessibility patterns, etc.).

Systems: A skill to understand how design patterns relate to a larger system and how the elements within the system are organized (e.g., task flows, information architecture, pattern libraries, etc.).

Prototyping: A skill to leverage design systems to create static or functional prototypes for user-testing and implementation (e.g., mockups, flows, prototypes, etc.).

3. Visual Design

The skills related to Visual Design encompass how to create visually attractive user interfaces within branding and style constraints. There are four distinct sub-categories for Visual Design:

Layout & Hierarchy: A skill to organize UI elements understandably while calling attention to essential actions and deemphasizing other UI elements.

Typography & Iconography: A skill to use type and icons as UI elements in effective ways.

Color: A skill to effectively use color and the meaning it conveys.

Motion: A skill to animate UI elements in meaningful ways that users understand.

4. Intentionality

The skills related to Intentionality encompass how to solve problems while working with others deliberately. There are three distinct sub-categories within this axis:

Process: A skill to consistently create successful design solutions using repeatable design techniques (e.g., Discover, Define, Design, Develop, Deploy).

Communication: A skill to communicate your work to others in understandable ways and at scale.

Collaboration: A skill to build trust with others and effectively collaborate with cross-functional teammates.

5. Drive

The skills related to Drive encompass a designer’s passion for the field of design and their willingness to lead others. You can find three distinct sub-categories within this axis:

Leadership: A skill to take ownership of a problem space and become the domain expert that others seek out.

Feedback: A skill to provide constructive feedback as well as be receptive to feedback from others.

Community: A skill to teach others to be successful and contribute back to the design community.

6. Self-Awareness

Finally, the skills related to Self-Awareness encompass one’s ability to know who one is and how one can improve. This axis has three distinct sub-categories:

Strengths: A skill to understand one’s strengths and how to promote them.

Weaknesses: A skill to understand one’s weaknesses and how to improve them.

Growth: A skill to continually seek out new ways to improve as a designer.

Phew! Let’s take a moment to pause and regroup here. I feel like I just walked up 19 flights of stairs after typing that section out. Panting and regaining breath. There is a total of 19 skills listed above. And, again, all of these skills are shared between every product designer. Do you see where this is going?

To level up, you must focus on one of the 19 skills above and create an actionable plan to strengthen the skill.

Danger! Product Designer. Danger!

You may feel overwhelmed by the six design axes and the many skills within each axis. “How could one designer be strong in all 19 skills!?” The answer simply is, “one cannot be strong in every skill.” You should never look at the design axes as a checklist because of this fact. Never ever ever. Instead, accept that you’ll be strong in some of these skills and weak in others, and that’s what makes your skill-set unique.

While we share all these skills, we do not share the same proficiencies in each and this is what makes us all unique. Some may be developing a skill while others are strong in it. Our uniqueness is why it’s all the more important to help lift each other up. Recognizing our unique talents will help us build a stronger, more inclusive design community.

Oh! And not every design skill fits perfectly into the six design axes. So it’s an imperfect framework for describing the ladder for all product design disciplines. For example, sound design is an integral part of mobile design, but this skill isn’t perfectly captured in the axes. It kind of fits in mobile patterns, but not neatly.

Not to mention, the design industry is ever-evolving, and new skill requirements are formed every day in emerging tech like Web 3.0, Metaverse, VR, and Wearables. So, though the design axes will remain the same, you can be confident that skills will continually evolve along with the industry, and so should your skills to remain relevant as a product designer. But that’s another article for another day.

Key Differences Between Junior & Senior Levels

I don’t believe I’ve specifically mentioned this yet, but when referring to “Junior” vs. “Senior” levels, I’m referring to lower-levels vs. higher-levels as two distinct buckets. These two buckets make it easier to draw generalizations and use blanket metaphors, which we’ll do next.

These are the key differences you’ll discover when comparing Junior and Senior levels to one another. All of these differences stem from a designer’s proficiency in the six design axes and are an outcome of becoming a stronger product designer. We’ll begin with Project Scope first.

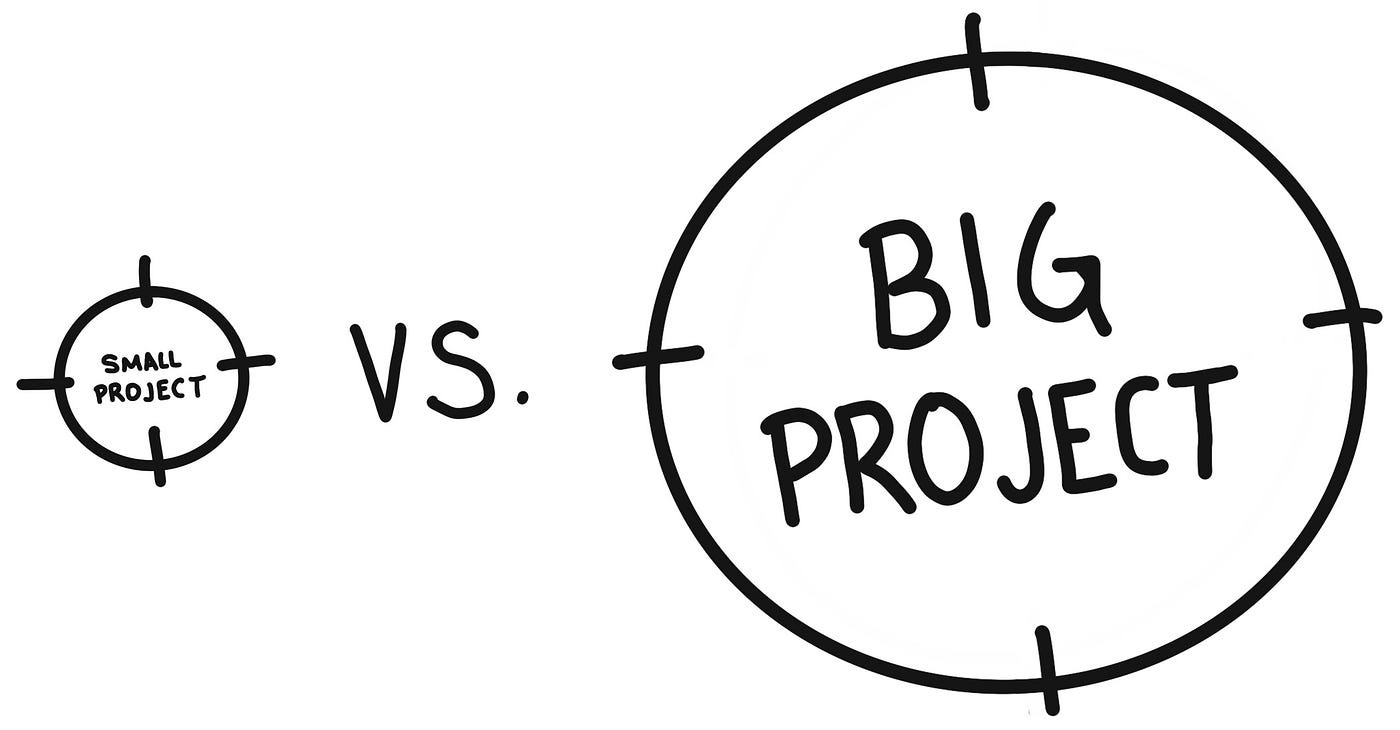

Project Scope

Junior designers will often work on projects that are smaller in scope. These projects are more bite-sized and manageable for inexperienced designers as they have fewer variables to consider and are more self-contained. In comparison, Senior designers will often own large projects with many variables to consider and stakeholders to keep aligned. Experienced Senior designers will know how to juggle a large project's variables while remaining organized (and somewhat sane. Lol.).

As Junior designers progress in their careers, their project’s scope will become larger and larger until the scope is megalithic. This shift in scope is an excellent time to check in with your manager and ask for a promotion. If you can prove that your project’s scope has increased while you remain an effective contributor, you’re a strong candidate for promotion to the next level.

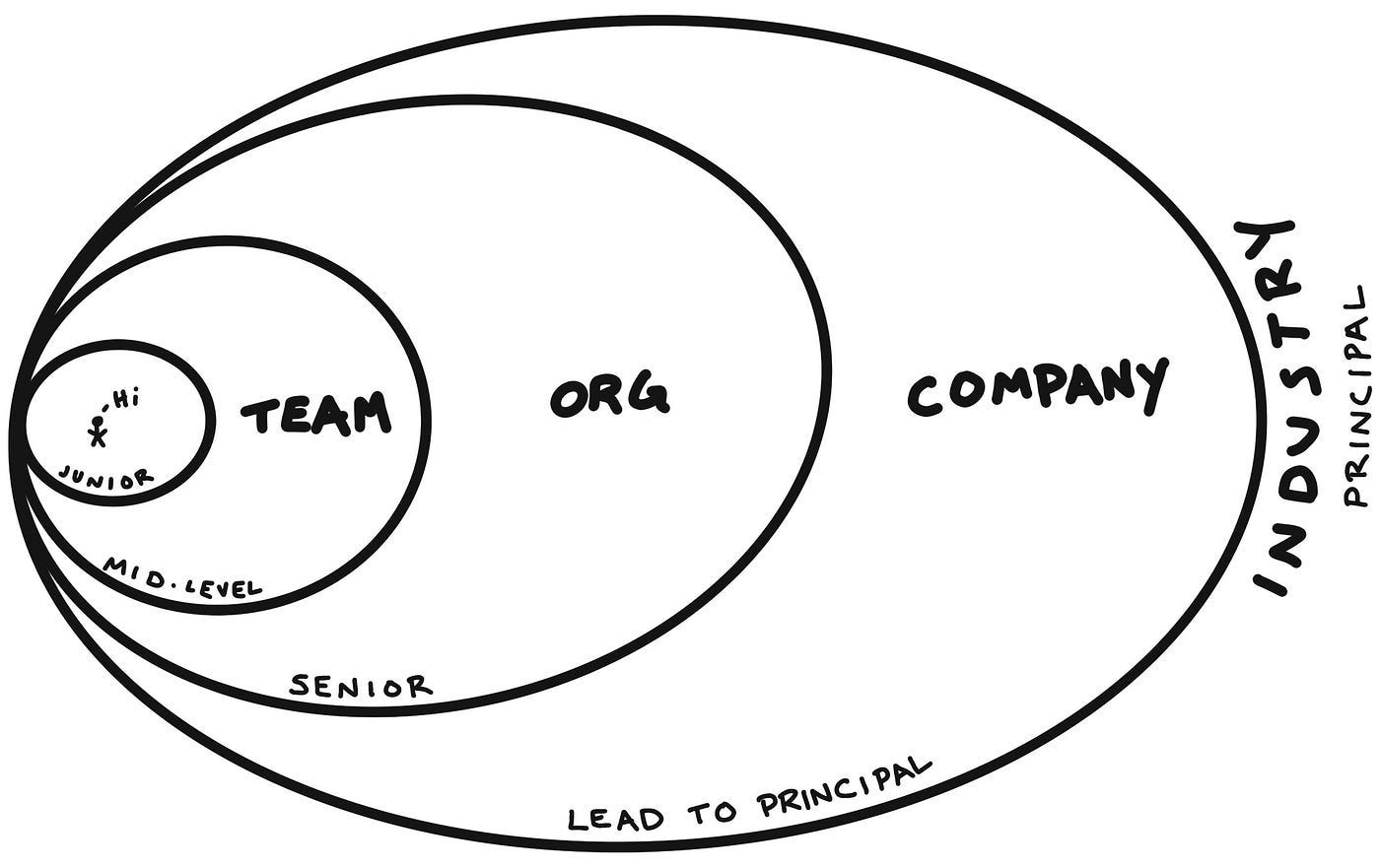

Influence Radius

The next key difference is a designer’s ability to influence others. A Junior designer first begins by influencing their behaviors and knowledge. Then, as Junior designers graduate to the upper levels, their influence also begins to impact others.

The first external influence area is within their immediate team. A Junior designer's opinion (i.e., designs) is heard and adopted by the people they work with directly. At some point, a designer’s external influence will trickle into the organization in which the team sits, marking them as someone with Senior qualities. Teammates on partner teams will seek out the opinion of these more Senior designers.

Eventually, a designer’s influence transcends the organization, and their impact will reach the entire company. This moment is when a designer shapeshifts into a mythical unicorn and flies off into the proverbial sunset. But, of course, in reality, influencers at this level are few-and-far-between, hence why they’re considered unicorns. Not to mention how incredibly subjective this company tier of influence is. But I digress.

If you find yourself consistently sought after by other organizations within your company or external companies, the chances are high that you’re a Senior designer. This influence is yet another moment to speak with your manager about a promotion.

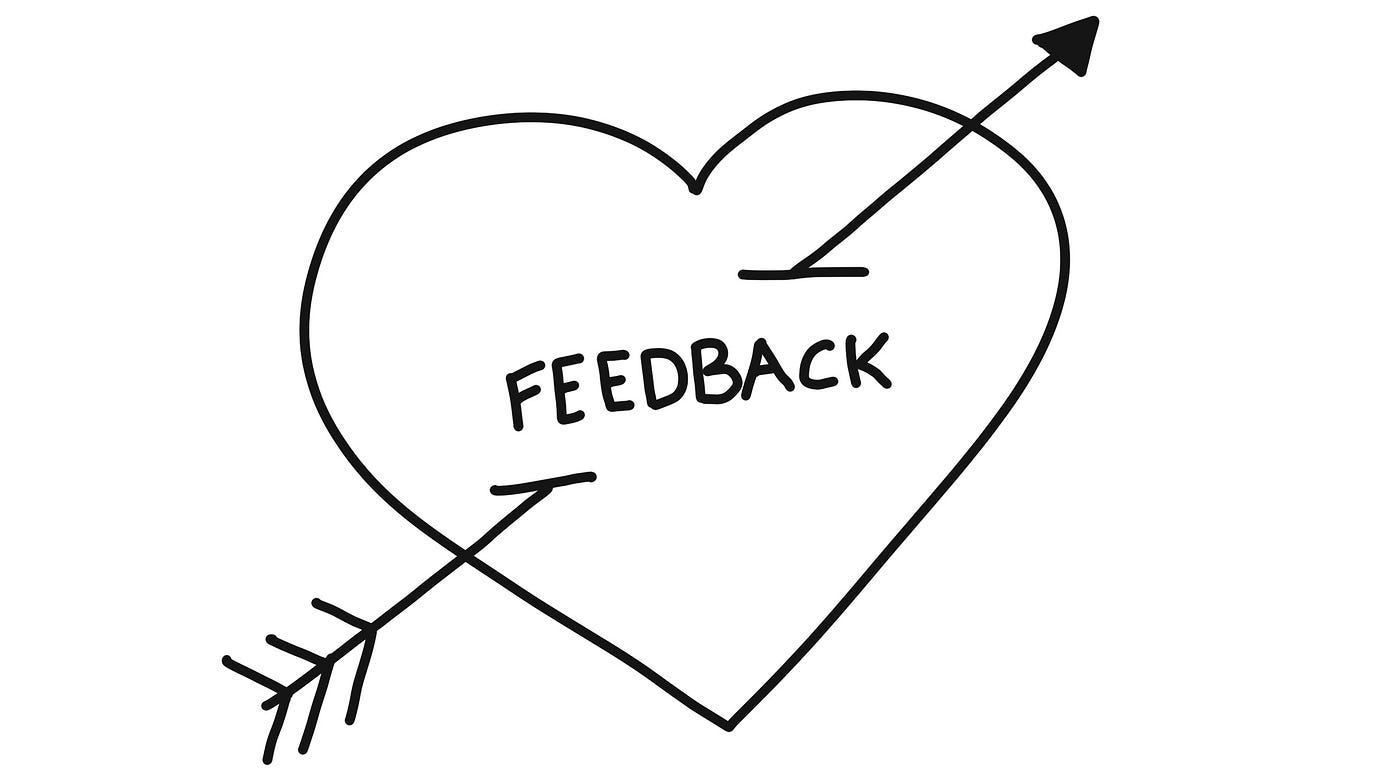

Truth Seekers

Feedback is a critical input for designers and is “a gift” in our industry. It’s a major driving force for how we iterate on our designs and gauge whether we’ve created something successful, which is why we collect so much of it.

Early on in a designer’s career, they will listen to all feedback and treat it equally. However, inexperienced designers have not learned the skill of filtering valuable signals from noise in the feedback they receive. The mistake of using feedback noise as directional input for design iteration can lead Junior designers to incorrect design solutions.

Experienced designers at the Senior level still welcome “the gift” of feedback but have developed a way to filter out feedback noise from the valuable signals. They ask direct questions and seek out objective truths to guide their design decisions. They recognize that not all feedback sources are equally valuable and prioritize design decisions accordingly.

Truth seekers are domain experts and often called upon for their opinion and direction. If this sounds like you, consider mentioning this to your manager.

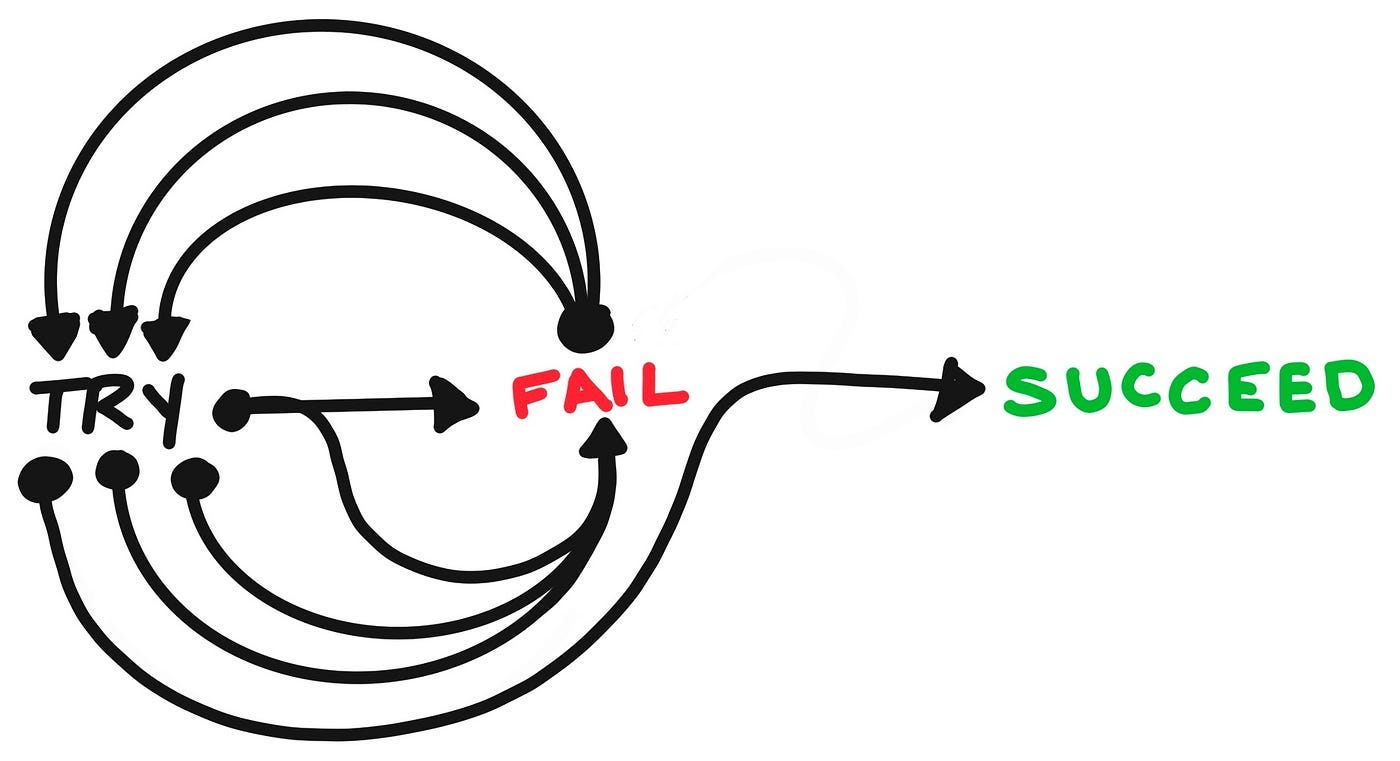

Embrace Failure

Failing can be painful. It can slow you down or cause a designer to decide to quit the profession outright. Resilience is the next factor that separates Junior designers from Senior designers.

Senior designers are callused and have built up a resilience towards failure. They’ve successfully solved many design problems, but not without failing time and time again. This resilience only comes with experience and determination to succeed.

On top of that, Senior designers have learned to fail faster. Because they’re chasing successful design solutions so often, they move as quickly as they can towards failure in hopes of finding success. As a result, they become more aware of what successful design solutions look like and become more confident in their work over time.

Designers who can demonstrate this often have higher design outputs than others. If you fail less often than your peers and continually arrive at successful solutions at breakneck speeds, it’s time to speak with your manager about a promotion.

Concrete vs. Ambiguous Projects

Well-defined problems that have been solved countless times by competitors are great projects for Junior designers to learn and grow from. These projects have concrete problems with clear solutions. In addition, junior designers can leverage existing product playbooks for bringing a product to market. A great example of this is e-commerce, which already has many great design examples out in the wild.

The ambiguous and uncharted problem spaces are where Senior designers shine. Examples of these platforms are VR, Wearables, IoT, etc. Because these problem spaces are relatively new to the design world, the only way to create successful designs is to be a trailblazer and experiment. In addition, ambiguous problem spaces require a designer to be proficient in many design skills. This proficiency in many skills is why it’s often difficult to break into these new design worlds as a Junior designer.

Suppose you find yourself smack-dab in the middle of uncharted design territory without clear guidance, and you consistently design successful solutions. In that case, it’s time to speak with your manager about a promotion.

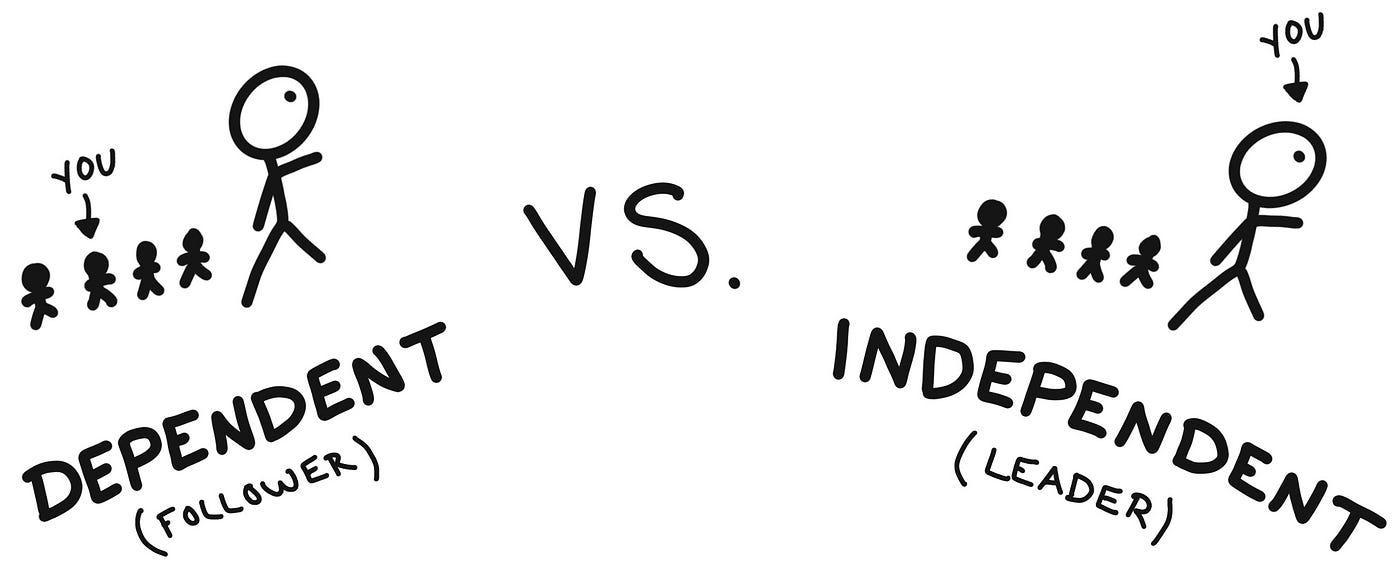

Autonomy

This one might be obvious but cannot go without saying. Junior designers are most often followers at the beginning of their career as they learn the ropes. They’re followers because they’re still building core design competencies and require others to guide them to success. Every designer requires some amount of hand-holding at the beginning of their career, and it’s not until they gain enough experience that they have the confidence to lead.

Senior designers, on the other hand, are experienced and not shy about leading others to success. They have complete ownership and understanding of a problem space, and others seek their advice and trust their opinion. They’re flexible and can coordinate groups of people and effectively collaborate with their team. They find ways to build community and frequently mentor Junior designers to help them level up.

A promotion is imminent if you exhibit any of the qualities mentioned earlier.

The Career Plan

Now that you know the fundamental building blocks (i.e., design axes) of the career ladder and the key differences between the levels on the ladder, we’ve arrived at the most critical section in this entire article. Next, we’ll dive deep into the importance of a career plan and how to create one.

Read on this guide: